Moral exoskeletons

December 22, 2020

I originally wrote this for Modern Design and Modern Culture, a class taught by Maggie Taft in the spring of 2020. One of my last classes in college, and easily one of my favourite. The assignment was to present an exhibition centered around a theme of our choosing. I chose to write about how buildings guide our daily social lives, and do so in (un)intentionally opinionated ways. I had a lot of fun exploring this theme, however briefly. Something to continue thinking about…

We all know about the internal human skeleton of bones, but what about the external skeleton within which we live our lives? The one made of walls and floors and hedges and distance?

There is no doubt that the built environment influences our bodies. Our doors decide who gets to go where, our windows consent who gets to see what, and our streets are maps that become territories. Beyond merely influencing our bodies, there is the growing realization that our built environment also influences our cognition. Minds do not exist in limbo – cognition is embodied. The built environment shapes our embodied experience, and thus shapes our embodied cognition.

The members of the 20th century progressive education movement are perhaps the most prominent believers of buildings as cognitive exoskeletons. As noted in New Learning Spaces and Places, “learning spaces must reflect and assist the curriculum, and as the curriculum takes new forms the environment must allow for change and for varied means of learning.” This design vision results in principles such as the principle of spatial variation and flexibility: “a schoolhouse should provide options in the sizes and shapes of sub-spaces so that people can comfortably gather in twos or fours, in groups of 10 or 20 or 100.”New Learning Spaces & Places (Minneapolis, 1974)

The conscious design of cognitive exoskeletons is nothing new. Consider, for instance, the circular paths of the Borobudur along which pilgrims circumambulate.Borobudur (Khan Academy) What is novel is designing cognitive exoskeletons for daily life. The implicit moral belief that today is a religious experience. And tomorrow. And the day after tomorrow…

When cognitive exoskeletons are truly lived in, they become moral philosophies in and of themselves. This is true whether or not they are consciously designed as cognitive exoskeletons. They encourage certain ways of living; they opine on how life should be lived. Consider what the streets of Chicago tell you. Most Chicago streets are wide and straight, allowing cars to travel at relatively high speeds. Most of them don’t have bike lanes. The streets of Chicago tell me that I should drive, not bike.With that being said, Chicago is probably one of the more bikable American cities.

Those who conciously design cognitive exoskeletons are thus moral philosophers as well as architects. This is certainly true for Lawrence Perkins, who designed Crow Island School to protect little kids from big kids if “the big kids wanted to play some boisterous, rough game.”Oral History of Lawrence Bradford Perkins (Chicago, 1986)

I’m particularly interested in what buildings have to say about how I should relate to others. In this exhibition, we will present this question to four notable built environments slash cognitive exoskeletons slash moral philosophies of the 20th century.

Crow Island School

Perkins, Wheeler & Will, Saarinens.

Winnetka, IL, 1940.

The Crow Island School is a shrine to progressive education. It embodies many of the principles laid out in New Learning Spaces and Places, inlcuding the principle of spatial variation and flexibility: “a schoolhouse should provide options in the sizes and shapes of sub-spaces so that people can comfortably gather in twos or fours, in groups of 10 or 20 or 100.”New Learning Spaces & Places (Minneapolis, 1974) Groups of two and four huddle around circular tables in classrooms. Each classroom in Crow Island is a peninsula, flanked on each side by an ocean of open green space. This insulates each classroom from the rest of the school, thereby establishing each classroom as a safe space of 10 or 20 children. Furthermore, children are separated by age group into three wings, each with their own playground. This protects little kids from big kids if “the big kids wanted to play some boisterous, rough game.”Oral History of Lawrence Bradford Perkins (Chicago, 1986)

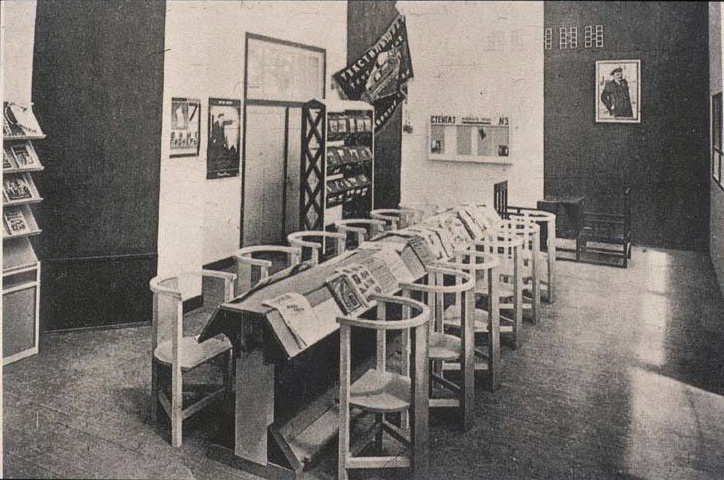

Worker’s Club

Rodchenko.

Paris, 1925.

Workers are sat along a single long table. In contrast to Crow Island, the workers have no choice in social group – they’re all in it together. If multiple conversations break out, each conversation is within earshot of the other. An interesting feature of the desk is the reading leaf. Notably, it seems like you can only switch your section into “reading mode” if you switch the entire table into “reading mode.” Thus the private work of reading becomes communal; each worker reads unprotected from the careful watch of their comrades. In lieu of supervision by a capitalist, there is supervision by your comrades.

Model for the Plan Voisin

Le Corbusier.

Paris, 1925.

The Plan Voisin is a broad daylight assault on the Arendtian public sphere. The cruciform shape means that each floor is only hallway and apartments, with no room for a central common space. Moreover, the stratospheric heights of the skyscrapers destroys the Parisian street as a forum that blends private and public spheres. Look outside your window from this height, and you will not see human life – only specks semi-stochastically milling about like worker ants. Like workers in Rodchenko’s Worker’s Club, residents of the Plan Voisin have no choice in social group. Unlike the Worker’s Club, the only option offered is the private sphere. The Plain Voisin is perhaps best described as the assembly line philosophy of social life, advocating that people should leave their private bubbles only to take their place on the economic assembly line, and for no other reason.

8 House

Bjarke Ingels Group.

Copenhagen, 2010.

8 House is a rejection of the template put forward by Le Corbusier for high density housing: 2D planes glued together with 1D elevators, with no space for public life. Instead, 8 House places apartments along a ramp, creating a truly continuous 3D neighbourhood that is an intentional imitation of a Mediterranean mountain city such as Granada. Like Crow Island, this ramp offers residents a choice in social groups. Many homes are on a single level and within eyesight of each other, thus reducing the friction between different homes. The fact that the ramp is open air further reduces social friction, providing a pleasant low-pressure space to meet neighbours and chat. The fact that homes are right on the ramp further blends the private and public spheres, lowering the barrier between the two. The ramp is a vision for public-private fora in high density housing, an evolution of the city street that will hopefully continue to evolve.